By Francesca Politi - JUMP team

The desire to learn through exploration is not a new phenomenon, it also provides a link to the past. During the 17th and 18th centuries many cultural pilgrimages were taking place through Europe, the cradle of Western civilisation. This event was called the Grand Tour, a trip undertaken by upper-class young European men. Travelling by carriage, and in some portions by foot, these tourists’ aim was to learn about the art, architecture and culture of antiquity. Italy was an attractive destination but at that time Calabria was difficult to access, little developed and so rarely visited by Grand tourists. We have to wait until the 19th century to see the region in the itinerary of some intellectuals; before that, few ventured far into Southern Italy, the toe of the boot.

In the eyes of travellers of the past the characteristics of Calabria revolved around the expression «we suffer and enjoy»

The logistical difficulties were offset by the enjoyment of the exceptional nature of the landscapes. A direct result of these travel experiences were often letters, diaries, reports that offered to the public an experience in the glories of this still-forgotten corner of Italy.

Among the tales of ancient tourists who adventured in the Southern area of Magna-Greek origins, one of the most remarkable is from the Victorian novelist George Gissing, whose pen gave birth to “By the Ionian Sea: Notes of a Ramble in Southern Italy”. A brief but eventful journey through the sea and the mountains, the orange groves, ruins, small dusty towns, hotels, and people that he observed on his journey. The towns described include Taranto, Crotone, Catanzaro, and Squillace. This enabled him to fulfill his desire to view the sites and old ruins of Magna Graecia and to visit the classical cities he called his land of romance.

“The names of Greece and Italy draw me as no others; they make me young again, and restore the keen impressions of that time when every new page of Greek or Latin was a new perception of things beautiful. The world of the Greeks and Romans is my land of romance; a quotation in either language thrills me strangely, and there are passages of Greek and Latin verse which I cannot read without a dimming of the eyes, which I cannot repeat aloud because my voice fails me. In Magna Græcia the waters of two fountains mingle and flow together; how exquisite will be the draught!”

Another travel report worth mentioning is “Old Calabria” written by Norman Douglas. Tracing an adventurous route from the promontory of Gargano in the north – linked in ancient times with Byzantium – to the southern tip of Aspromonte, he scaled vast mountain ranges, trekked through dense forest and crossed remote and often dangerous countryside.

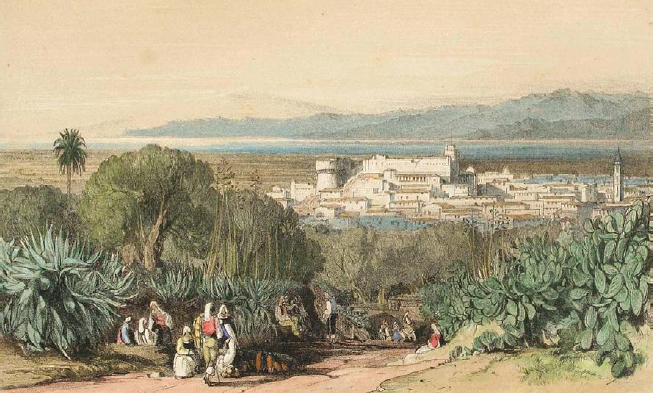

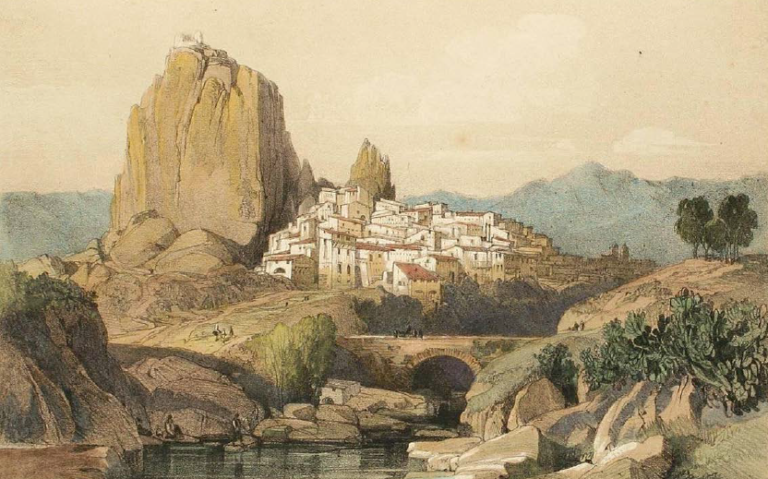

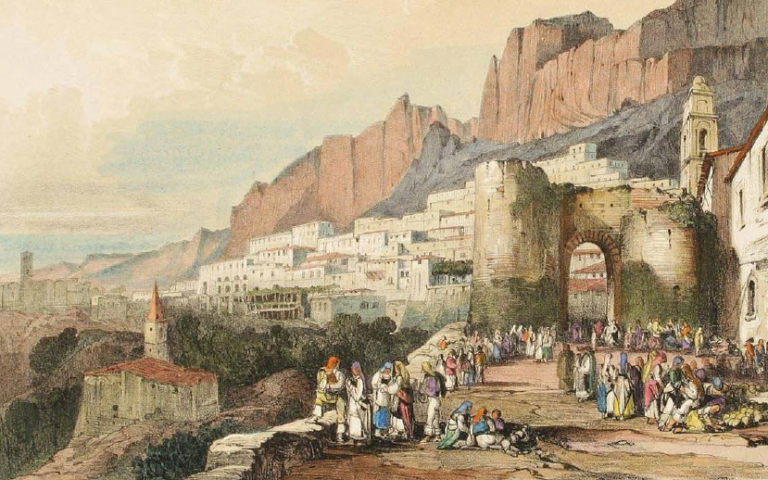

Lastly, it is in the province of Reggio Calabria that the writer Edward Lear created “Journal of a Landscape Painter in Southern Calabria“, a brilliant integration between textual and visual narrative. The result of his 40-days pedestrian tour are precious lithographies which documented each day of his journey and published five years after in 1852. This collection compose an historical picture of southern Calabria at that time: the duality of the Calabrian land, divided between the harshness of mountains and its peculiar vegetation (we can find illustration of botanical subjects, like prickly pear plantations or aloe plant) and the gentleness of coast.

From his experience an evocative project was born, a twitter profile that can make you relive the emotions of Lear’s journey through the Aspromonte valleys and the deep blue of the Ionian Sea, as if he was a travel blogger! Interesting to see how much has changed – both in these locations as well as the way we travel and interact with the different venues we visit.

Sources:

- ArcHistoR (Extra n. 4/2018): Voyage pittoresque. II. Osservazioni sul paesaggio storico della Calabria

Pictures:

- Figura 1. Edward Lear, Reggio, litografia colorata (Lear 1852, p. 6).

- Figura 2. Edward Lear, Palizzi, litografia colorata

(Lear 1852, p. 268) - Figura 3. Edward Lear, Stilo, litografia colorata

(Lear 1852, p. 110).