By Jennifer Meléndez-Luces, ESID Liceo La Paz, Spain.

I still remember my astonishment that day when walking through the Faculty of Modern Languages of the Adam Mickiewicz University I came across a small poster announcing the holding of a session on Rosalía de Castro. I was aware of its importance in Galicia and Spain, but I did not know that in Poland, that country that I had decided to make my home for 9 months, they knew who that woman, always feeling homelessness and black grief, had been. I suppose that that purple poster was not only a warning but also – at least for me – a discreet but at the same time direct way of telling me that, on many occasions, we look outside what, if not almost always, we have next to our home.

Until that moment, I only knew about Rosalía de Castro what my Galician and Spanish language teachers had insatiably told me about her at school… However, I understood that I had not spent enough time reading her, understanding her, feeling her… And perhaps it was there, in the midst of that maelstrom of feelings – between being far away, missing home and wanting to stay and live in that instant forever – when I finally, was able to understand the complexity with which Rosalía began to weave her verses back in 1857.

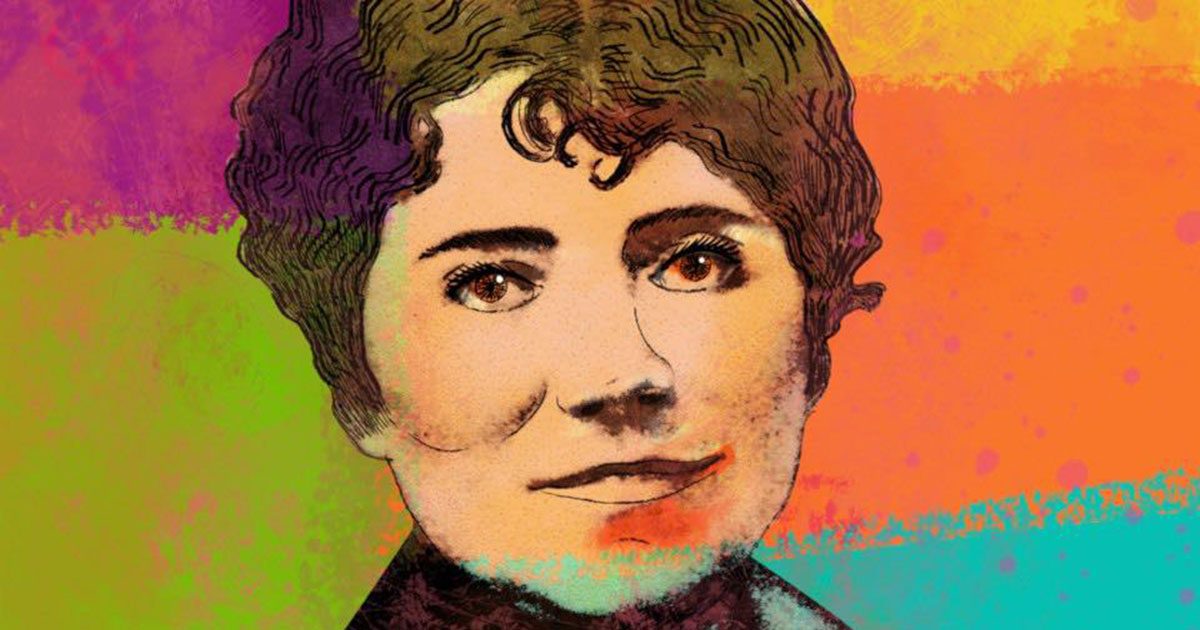

Years later, walking through the streets of San Francisco (USA), I came across a mosaic that completely covered the facade of a school near The Painted Ladies. Each piece of tile was an iridescent turquoise blue and, between unfamiliar faces, I met again with a familiar face that, once again, invited me to travel back to my adoptive home, Galicia, for a few seconds. And there, again, looking straight at that image of Rosalía de Castro, I once again understood that the trail that she had left as a writer and as a woman had been, and continues to be, infinite. So infinite and brilliant that her words had the ability to make the Galician language, her mother tongue, resurface in the 19th century from centuries of darkness like a phoenix.

At this point, we need to understand that, despite the fact that the Galician language enjoyed high splendor during the Middle Ages, during the fourteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Reign of the Catholic Monarchs) it was only used in order to carry out oral communication in the family and rural environment. This caused, in turn, the disappearance of the Galician language from the written tradition, which also led to its disappearance in other areas of daily life, such as the publication of official and public documents. As it was a decadent period for the Galician, this time received the name of “Dark Centuries “.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, due to its exclusive status as an oral language, it prevented the Galician language from participating in the process of fixation and standardization that at that time occurred with other languages from the Latin tradition. In this way, while in other Romance languages (Spanish or Portuguese, for example) the first grammars and dictionaries that incorporate Latin and Greek cultisms into their lexicon began to appear. Therefore, Galician suffered a linguistic impoverishment. This meant that Galician did not have its first grammar until the second half of the 19th century.

If the situation had not been positive for the Galician language during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it would be less so during the eighteenth century, since the “desgallizamiento” process and incursion of Spanish will be extended – even more – with the arrival of bourgeois families that came to Galicia in order to promote industry and commerce as well as the establishment of the Borbon monarchy.

Fortunately, the situation of darkness began to see the light at the beginning of the XIX century thanks to the ideological and cultural evolution that will propitiate a new literary splendor that today is known as “Rexurdimento” which took place in 1863, the year in which Rosalía de Castro publishes her book Cantares Gallegos.

At the dawn of the 19th century, the population of Galicia was mainly from the rural world and the Galician economy depended – almost exclusively – on agriculture and the good peasants who worked the fields of the feudal lords. The situation of poverty that Galicia faced at that time led many Galicians to leave their homes and travel to the interior of the peninsula in order to find a better living situation.

However, in 1808 the invasion of the French took place leading – in turn – to the War of Independence (1809 – 1812) and it was at that time that Galician was again written in order to mobilize the peasants and urge them to fight against the French. In the years to come, political texts that collected the disputes between absolutists and liberals in the Galician language began to appear in various journals to facilitate their dissemination among the popular classes. During that same period of time, in Europe the cultural and literary movement known under the name of Romanticism arose, which in Galicia facilitated the creation of a favorable climate among the intellectuals of the time, since it encouraged them to study the history of peoples and traditions as well.

The spirit of rebellion was one of the maxims promulgated by Romanticism, which led to the appearance in Galicia of a new cultural, ideological and political movement known as Provincialism (1840 – 1854). This new current or movement was made up of upper-middle class intellectuals who used the press to publicize their ideals. One of the most notable events of this movement was the participation in the uprising of General Solís in 1846, which led to the rebellion of the kingdom of Galicia against the centralism established by the monarchy of the time. However, this uprising against the monarchical system failed and ended with the execution of those taking part in it. Today they are known as “Mártires de Carral”.

Regarding Literature in the Galician language, a new stylistic trend known as the Precursors emerged, formed by Juan Manuel Puntos and Francisco Añón. However, it will not be until later with the arrival of writers such as Manuel Murguía (“frasquiño de esencia”), Eduardo Pondal or – the protagonist of our article – Rosalía de Castro, when the Galician language can finally glimpse the resurgence of his lyrics.

But who was really Rosalía de Castro?

Rosalía de Castro, today a symbol of feminism “from one border to another”, was born in Santiago de Compostela in 1837. She had been the fruit of a loving relationship between a woman who belonged to the upper bourgeoisie and a clergyman. Her birth would mark Rosalía’s life forever, since her father could never recognize her as his legitimate daughter. During her first years of life, Rosalía will live with her paternal aunts in a village near Santiago de Compostela. Later, in 1850, her mother decides to take care of her and they go to live in Santiago. It is in this Galician city where Rosalía de Castro begins to frequent progressive environments related to the spirit of provincialism.

In 1856, Rosalía traveled to Madrid and it was in the capital of Spain that she published her first work in Spanish under the title La Flor. In this city she met the historian of Coruña origin Manuel Murguía with whom she later married in 1858 and with whom she had 7 children, of which two died as children. During her marriage, she is forced to accompany her husband to different geographical locations in Spain until they finally settle in Simancas (Castilla y León) where her husband works as Head of the Archive of the Kingdom of Spain. During the seven years that they spent in this location, Rosalía composed her book Cantares Gallegos – the first work published entirely in Galician and the first work of Galician origin of which more translations have been made – as well as many of the poems that make up Follas Novas.

Years later (1871), Rosalía definitively returned to Galicia after the appointment as Head of the General Archive of Galicia by her husband Manuel Murguía. At that time, Rosalía and her family moved into a single-family home located in the old city of A Coruña. Later they settle in various locations in Galicia such as Santiago, Lestrove and, finally, Padrón. It is in the latter where, unfortunately, Rosalía will live her last years of life under the effects of a painful illness. It is here where, in addition, she will finish her book of poems Follas Novas and where she will write En las Orillas del Sar, the latter in Spanish.

Rosalía de Castro and her impact today:

As we have previously introduced, Rosalía was – without a doubt – the author who marked a turning point for the rise of the cultural and literary movement known today as Resurgimiento. However, her work was not always well regarded and it is in fact today that Rosalía regains the importance that was denied her in the past. Today Rosalía seen from an international trajectory as a late romantic and as a pioneer of feminism. Ideology that clearly reflected in “Lieders” a small manifesto that she wrote in 1858 in which she defended independence, freedom and equality, in the same way that she spoke of the basic principles of her thought and her ideal of feminism.

It has been 184 years since Rosalía de Castro left a wake in the sky after being recognized as a “national writer of Galicia”. A trail that speaks of a horizon of hope, dignity, freedom, independence and equality and that makes Rosalía remain today more alive than ever.